For those of us who grew up with Dungeons & Dragons, it is easy to take the polyhedral dice of gaming for granted. Dice had played an integral role in gaming since Prussian wargamers of the early nineteenth century first developed combat resolution tables. Those games and the many works they influenced, however, relied exclusively on 6-sided dice, apart from a few experimental dead-ends (like Totten's 12-sided teetotum in the late nineteenth century). When modern hobby wargaming culture began in the 1950s, it too stuck with 6-siders: the first Avalon Hill game (Tactics, 1954) requires a "cubit" for combat resolution, and the miniature gamers who contributed to the War Game Digest similarly seemed content to rely on the d6. By 1970, however, polyhedral dice had begun to creep into the wargaming community, as we see in the advertisement above from a 1971 Wargamer's Newsletter. Why do we need those funny dice anyway? What purpose did they serve that an ordinary 6-sider couldn't?

Wargamers constantly reach for greater heights of realism in their simulations, and by the mid-1960s, they increasingly relied on actual military statistics to model their combat. Perhaps the most influential example of this trend is Michael J. Korns's book Modern War in Miniature (1966), a WWII-setting wargame which offers little by way of system other than tables aggregating real-world weapon behavior. Korns reduced these statistics to percentile probabilities: for example, a particular rifle might have a 70% chance to hit a target 200 yards away. But how to resolve those odds during play? There is no intuitive way to extract percentile results from rolling a small number of d6s, but Korns provided an appendix that gave the closest approximation, roughly 5% increments:

Korns's game proved very influential in the American Midwest, and took hold in the two communities where Dungeons & Dragons grew up: Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and the Twin Cities of Minnesota. For example, Mike Carr, a prominent Twin Cities gamer, incorporated the above table into his 1972 edition of his Fight in the Skies. In Lake Geneva circles, Leon Tucker, himself a professional statistician, advocated strongly for the use of Korns, but was dissatisfied with the means of resolving percentile probability. The need for greater realism demanded more than just approximations of 5% increments. This led to an outpouring of creativity as gamers developed all sorts of improvisational ways of getting percentile numbers: you could draw two cards from a deck with the face cards removed, or pick numbered poker chips out of a hat. Tucker himself proposed an elaborate apparatus involving a graduated tube with a stopper and colored beads as a part of his ongoing collaboration with Gary Gygax and Mike Reese towards a new post-Korns set of modern miniatures rules called Tractics.

Thus, late in 1969, when chatter began in the "Must List" of Wargamer's Newsletter about the commercial availability of 20-sided dice, these implements were presented as a means of generating percentile numbers: the advertisement from the Bristol Wargames Society refers to them as "percentage dice" and doesn't even say how many sides they had. This is an area where the exotic icosahedron excels, as the models sold at the time were numbered 0-9 twice, rather than 1-20. With two throws, one could therefore generate a number from 1-100. Gary Gygax was among the readers of Wargamer's Newsletter at the time, and thus it is unsurprising that he chimed in with a letter in the February 1971 issue saying, "I imagine that sales of 20 sided dice will pick up when Mike Reese starts selling the [Tractics] rules." Then d20 gets an early mention in the Tractics rules published in the fall of 1971.

This was not the first time that the use of 20-sided dice for wargaming had been proposed: Lenard Lafoka wrote an article late in 1968 that described the potential applicability of the icosahedron to wargames, but since readers would have no means of procuring one, Lakofka actually provided instructions on how to construct a 20-sided die out of wood or cardboard. The dice discussed in Wargamer's Newsletter in the early 1970s were available only from Japan or Britain, and for Americans ordering from either was a costly and lengthy proposition. Don Lowry, the publisher of Tractics, couldn't rely on an expensive and slow source for supplying the needs of his customers.

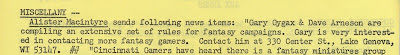

News of an American supplier of 20-sided dice began to spread in mid-1972 through wargaming zines like The Courier, as in the notice from Dion Osika above. The dice were also prominently featured in the first issue of the People's Computer Club magazine of October 1972, with an advertisement that showed a spinner and then five "superdice." Intriguingly, the supplier, Creative Publications of California, only sold their 20-sider in a set with four other dice: one of each Platonic solid. These five geometric shapes alone have a special property (that all of their faces, edges and vertices have the same relationship to their center of gravity) which makes them ideal as dice. Both the 6-sider and 20-sider are Platonic solids, and the list is rounded out by the d4, d8 and d12; all of these shapes have origins that go back into pre-history. The applicability of dice other than the d6 and d20 to wargaming was not clear off the bat; although Dave Wesely, in his work revising Totten, had gone on an epic quest to find a twelve-sided teetotum, ultimately his Strategos N rules did not require anything but d6s. Since the Creative Publications dice were comparatively inexpensive, Don Lowry began to stock them as a service to Tractics customers, initially without even a mark-up.

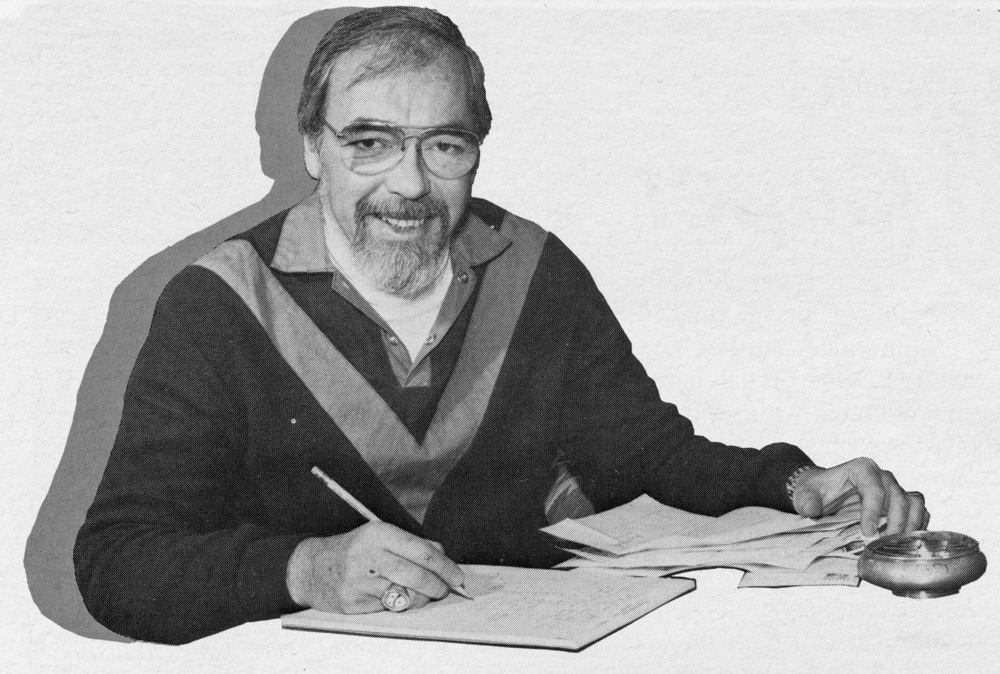

Gary Gygax frequently helped Lowry to promote new products in his mailer Lowrys Guidon, and with the arrival of polyhedral dice came Gygax's seminal June 1973 article "Four & Twenty and What Lies Between." In it, Gygax explains the probabilities that can be resolved with combinations of d4s, d8s and so on, though he concedes that "the most useful are the 20-sided dice." He knew they could be used for more than just generating percentile numbers: you can also "color in one set of numbers on the die, and you can throw for 5% -- perfect for rules which call for random numbers from 1-20." What would you use that for? Coincidentally, Gygax confides in that same article that he was "busy working up chance tables for a fantasy campaign game." That game, of course, was Dungeons & Dragons.

The first edition of Dungeons & Dragons made far less use of polyhedral dice aside from the d20 than later editions; the d4, d8 and d12 make only very rare appearances. Nonetheless, polyhedral dice quickly became a signature feature of D&D. They were moreover an early stumbling block when demand for the game was high: one could easily photocopy rules, but not dice. TSR continued to resell the Creative Publications dice, but at a considerable mark-up: initially $1.75, then $2.50, then $3.00. Many gamers therefore experimented with alternative methods for generating numbers, reminsicent of the Korns table above. Others eventually found the source of the dice and ordered directly from Creative Publications. By the 1980s, TSR had sufficient sales to strike aggressive wholesaler agreements, and it was only then that they augmented their sets of Platonic solid dice with a newcomer: the d10. In the years since, mad scientists like Lou Zocchi have produced all sorts of unusual dice, some more practical than others. Today, we can't imagine polyhedral dice without thinking of gaming, but their association with games is the sort of happy historical accident that frequently accompanies success.

Wargamers constantly reach for greater heights of realism in their simulations, and by the mid-1960s, they increasingly relied on actual military statistics to model their combat. Perhaps the most influential example of this trend is Michael J. Korns's book Modern War in Miniature (1966), a WWII-setting wargame which offers little by way of system other than tables aggregating real-world weapon behavior. Korns reduced these statistics to percentile probabilities: for example, a particular rifle might have a 70% chance to hit a target 200 yards away. But how to resolve those odds during play? There is no intuitive way to extract percentile results from rolling a small number of d6s, but Korns provided an appendix that gave the closest approximation, roughly 5% increments:

Korns's game proved very influential in the American Midwest, and took hold in the two communities where Dungeons & Dragons grew up: Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and the Twin Cities of Minnesota. For example, Mike Carr, a prominent Twin Cities gamer, incorporated the above table into his 1972 edition of his Fight in the Skies. In Lake Geneva circles, Leon Tucker, himself a professional statistician, advocated strongly for the use of Korns, but was dissatisfied with the means of resolving percentile probability. The need for greater realism demanded more than just approximations of 5% increments. This led to an outpouring of creativity as gamers developed all sorts of improvisational ways of getting percentile numbers: you could draw two cards from a deck with the face cards removed, or pick numbered poker chips out of a hat. Tucker himself proposed an elaborate apparatus involving a graduated tube with a stopper and colored beads as a part of his ongoing collaboration with Gary Gygax and Mike Reese towards a new post-Korns set of modern miniatures rules called Tractics.

Thus, late in 1969, when chatter began in the "Must List" of Wargamer's Newsletter about the commercial availability of 20-sided dice, these implements were presented as a means of generating percentile numbers: the advertisement from the Bristol Wargames Society refers to them as "percentage dice" and doesn't even say how many sides they had. This is an area where the exotic icosahedron excels, as the models sold at the time were numbered 0-9 twice, rather than 1-20. With two throws, one could therefore generate a number from 1-100. Gary Gygax was among the readers of Wargamer's Newsletter at the time, and thus it is unsurprising that he chimed in with a letter in the February 1971 issue saying, "I imagine that sales of 20 sided dice will pick up when Mike Reese starts selling the [Tractics] rules." Then d20 gets an early mention in the Tractics rules published in the fall of 1971.

This was not the first time that the use of 20-sided dice for wargaming had been proposed: Lenard Lafoka wrote an article late in 1968 that described the potential applicability of the icosahedron to wargames, but since readers would have no means of procuring one, Lakofka actually provided instructions on how to construct a 20-sided die out of wood or cardboard. The dice discussed in Wargamer's Newsletter in the early 1970s were available only from Japan or Britain, and for Americans ordering from either was a costly and lengthy proposition. Don Lowry, the publisher of Tractics, couldn't rely on an expensive and slow source for supplying the needs of his customers.

News of an American supplier of 20-sided dice began to spread in mid-1972 through wargaming zines like The Courier, as in the notice from Dion Osika above. The dice were also prominently featured in the first issue of the People's Computer Club magazine of October 1972, with an advertisement that showed a spinner and then five "superdice." Intriguingly, the supplier, Creative Publications of California, only sold their 20-sider in a set with four other dice: one of each Platonic solid. These five geometric shapes alone have a special property (that all of their faces, edges and vertices have the same relationship to their center of gravity) which makes them ideal as dice. Both the 6-sider and 20-sider are Platonic solids, and the list is rounded out by the d4, d8 and d12; all of these shapes have origins that go back into pre-history. The applicability of dice other than the d6 and d20 to wargaming was not clear off the bat; although Dave Wesely, in his work revising Totten, had gone on an epic quest to find a twelve-sided teetotum, ultimately his Strategos N rules did not require anything but d6s. Since the Creative Publications dice were comparatively inexpensive, Don Lowry began to stock them as a service to Tractics customers, initially without even a mark-up.

Gary Gygax frequently helped Lowry to promote new products in his mailer Lowrys Guidon, and with the arrival of polyhedral dice came Gygax's seminal June 1973 article "Four & Twenty and What Lies Between." In it, Gygax explains the probabilities that can be resolved with combinations of d4s, d8s and so on, though he concedes that "the most useful are the 20-sided dice." He knew they could be used for more than just generating percentile numbers: you can also "color in one set of numbers on the die, and you can throw for 5% -- perfect for rules which call for random numbers from 1-20." What would you use that for? Coincidentally, Gygax confides in that same article that he was "busy working up chance tables for a fantasy campaign game." That game, of course, was Dungeons & Dragons.

The first edition of Dungeons & Dragons made far less use of polyhedral dice aside from the d20 than later editions; the d4, d8 and d12 make only very rare appearances. Nonetheless, polyhedral dice quickly became a signature feature of D&D. They were moreover an early stumbling block when demand for the game was high: one could easily photocopy rules, but not dice. TSR continued to resell the Creative Publications dice, but at a considerable mark-up: initially $1.75, then $2.50, then $3.00. Many gamers therefore experimented with alternative methods for generating numbers, reminsicent of the Korns table above. Others eventually found the source of the dice and ordered directly from Creative Publications. By the 1980s, TSR had sufficient sales to strike aggressive wholesaler agreements, and it was only then that they augmented their sets of Platonic solid dice with a newcomer: the d10. In the years since, mad scientists like Lou Zocchi have produced all sorts of unusual dice, some more practical than others. Today, we can't imagine polyhedral dice without thinking of gaming, but their association with games is the sort of happy historical accident that frequently accompanies success.

.

.